This post covers my notes and findings from reverse engineering the Quick 6101A2

fume extractor's command protocol to integrate it into my other tools and

control it without the original controller. In part 1, we'll focus on analyzing

and parsing the protocol, mapping the sensor/control registers, then build a

simple terminal tool to monitor the fume extractor.

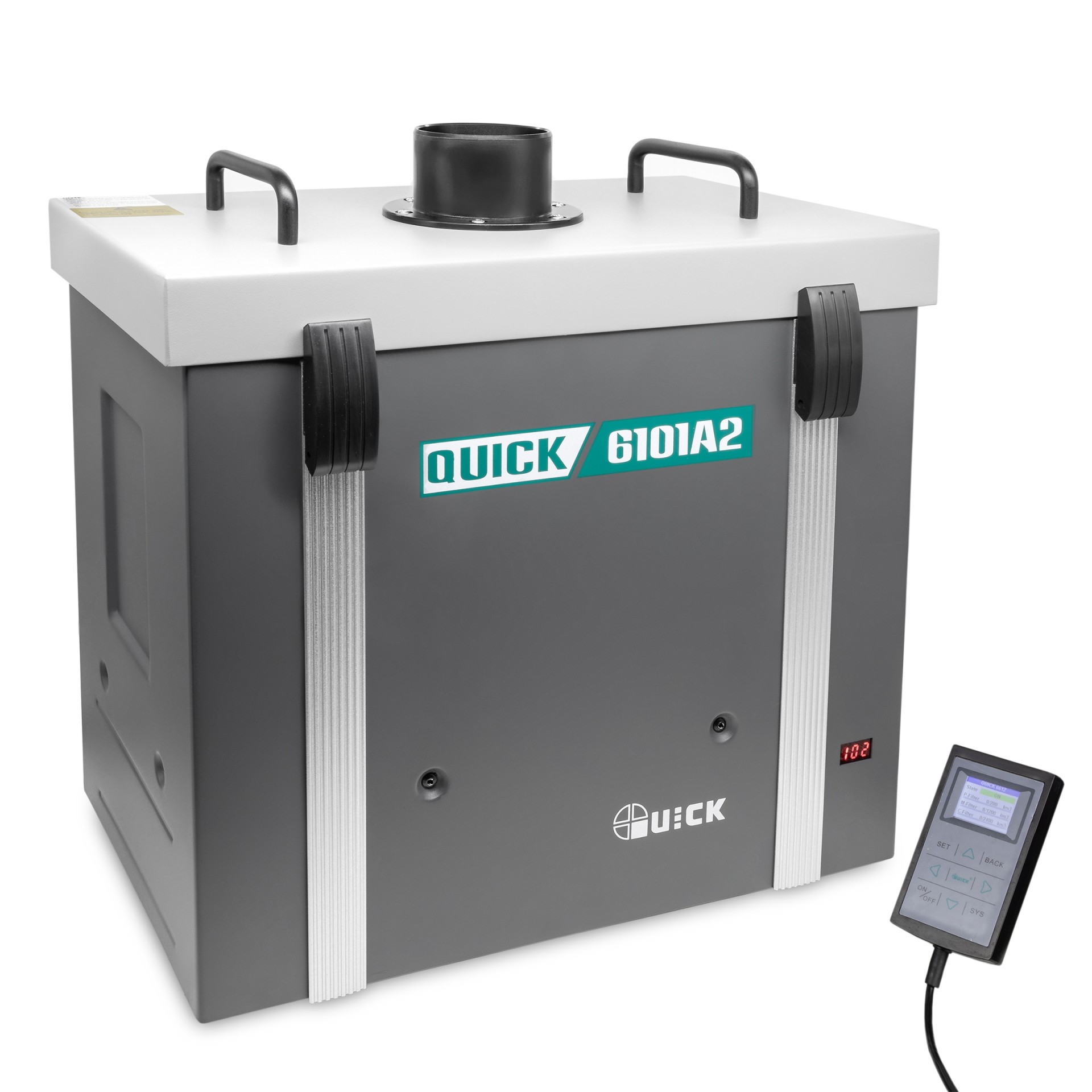

For a long time I had one of those cheap desktop fume extractors. They ship with

a coarse "filter" that feels more like a fume mixer than a device that actually

removes hazardous fumes. For light use they're fine, but lately I've been doing

more BGA reballing and rework, so I decided to upgrade to a proper HEPA unit and

went with Quick's 6101A2. I'd already

been happy with the build quality of their

861DW

hot-air station as well, and the price is hobbyist-friendly compared to JBC's

models, for example.

Quick 6101A2 main and controller unit.

Quick 6101A2 main and controller unit.

The fume extractor consists of the main unit that has the filters, motor, etc.,

and a wired remote controller that can turn the device on/off, change settings,

and show the airflow, filter stats, etc. It also has a connector for external

devices, like a soldering iron or a hot air station, so it can turn on

automatically when you pick up the iron. Of course each manufacturer has their

own proprietary port/protocol to interconnect these devices, so I cannot

directly connect my JBC soldering station to my Quick 6101A2.

I decided to reverse engineer the communication protocol to allow me to build a

proxy between my solder station and the fume extractor. The obvious starting

point would be the external tool connector, but unfortunately I don't have any

devices that support it at the moment. So I decided to look into the

communication between the main unit and the controller. It wouldn't surprise me

if the controller and the external tool speak the same protocol.

The connectors for the

controller and an external tool.

The connectors for the

controller and an external tool.

It's Always Serial

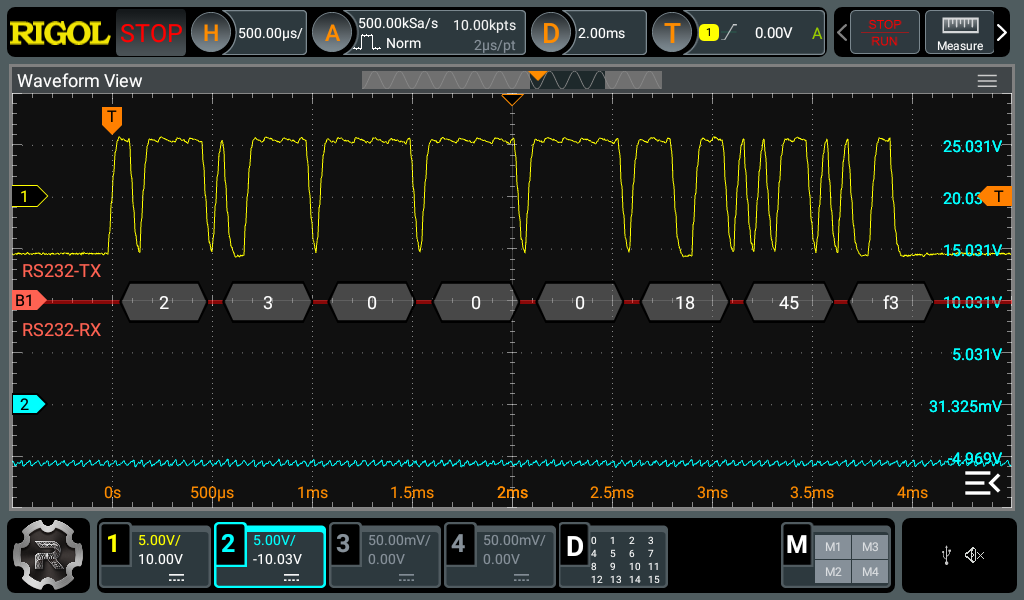

The first suspicious observation is that the controller is connected to the unit

with a USB-A cable. Using USB for something this simple sounds unlikely, and I

did not want to attach Cynthion

straight away in case it wasn't actually USB and I'd end up blowing the USB

analyzer. So I probed the data pins with an oscilloscope instead. As expected,

the signals look like RS-232, not USB, and they decode nicely into serial data

at 19200 baud.

The

decoded frame from the controller unit (19200; 8N1).

The

decoded frame from the controller unit (19200; 8N1).

The connector has this pinout:

| USB-A Pin | Signal | Notes |

|---|

| 1 | 5V | The base unit provides power |

| 2 | RS-232 | Controller's TX (D- in real USB) |

| 3 | RS-232 | Controller's RX (D+ in real USB) |

| 4 | GND | |

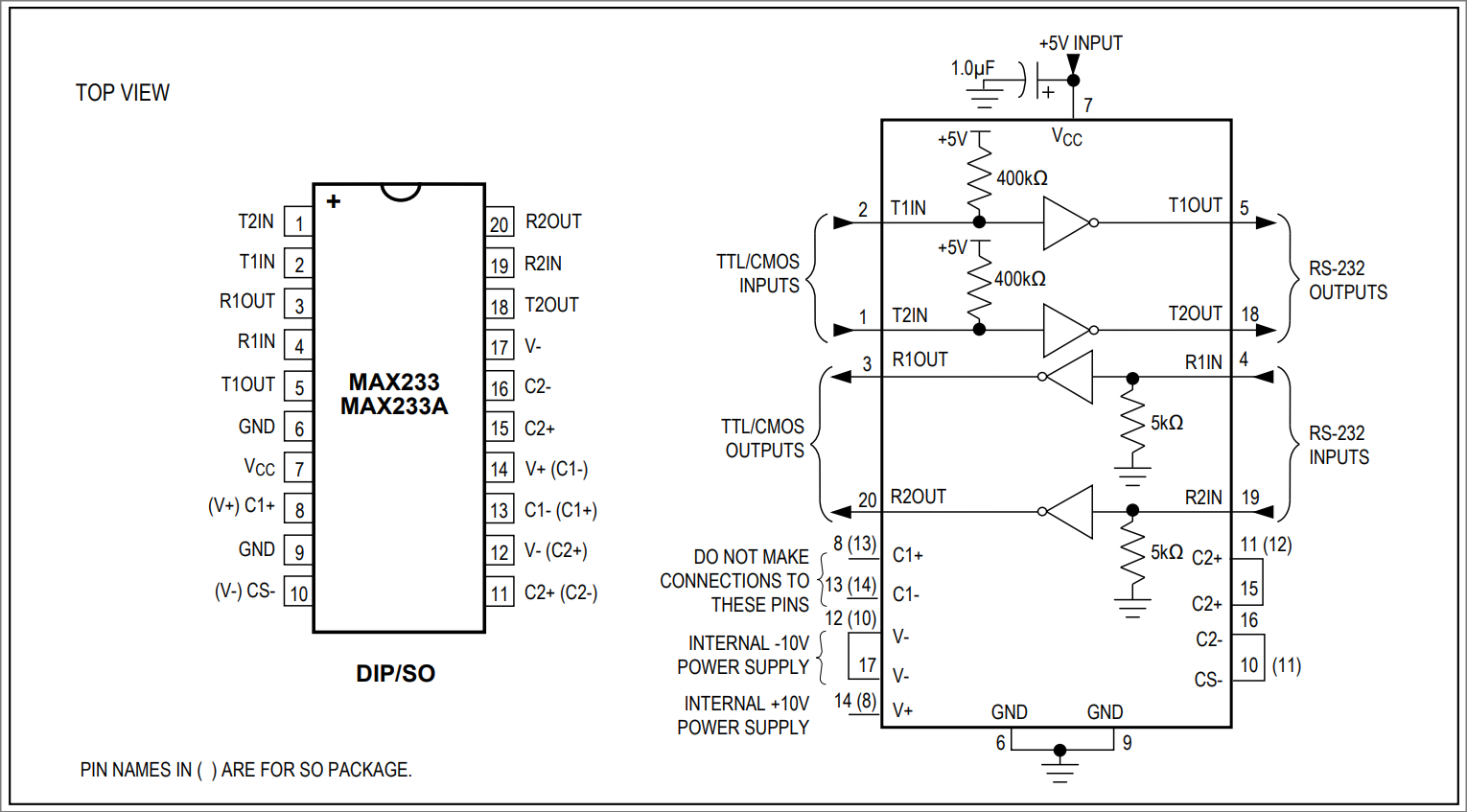

Before diving into figuring out what those bytes mean, I wanted a longer

capture. An oscilloscope isn't ideal for that. The simplest option would be a

USB-RS232 adapter, but we'd need two to capture TX and RX and then sync them,

which feels cumbersome. A logic analyzer is a better fit. Because this is real

RS-232 (±6 V in this case), the signal has to be level-shifted to TTL to avoid

blowing my logic analyzer. I had a

MAX233

(multichannel RS-232 driver/receiver) in my parts bin, which makes the

conversion easy since it doesn't need external capacitors or extra circuitry.

MAX233 Pin Configuration and Typical

Operating Circuit.

MAX233 Pin Configuration and Typical

Operating Circuit.

The typical operating circuit is more than enough to tap into an existing

RS-232 line as shown above. Here we connect Quick's TX and RX lines into RS-232

inputs (pins 4 and 19), and the logic analyzer to TTL outputs (pins 3 and 20).

That setup lets us capture a nice long stretch of communication between the

controller and the unit.

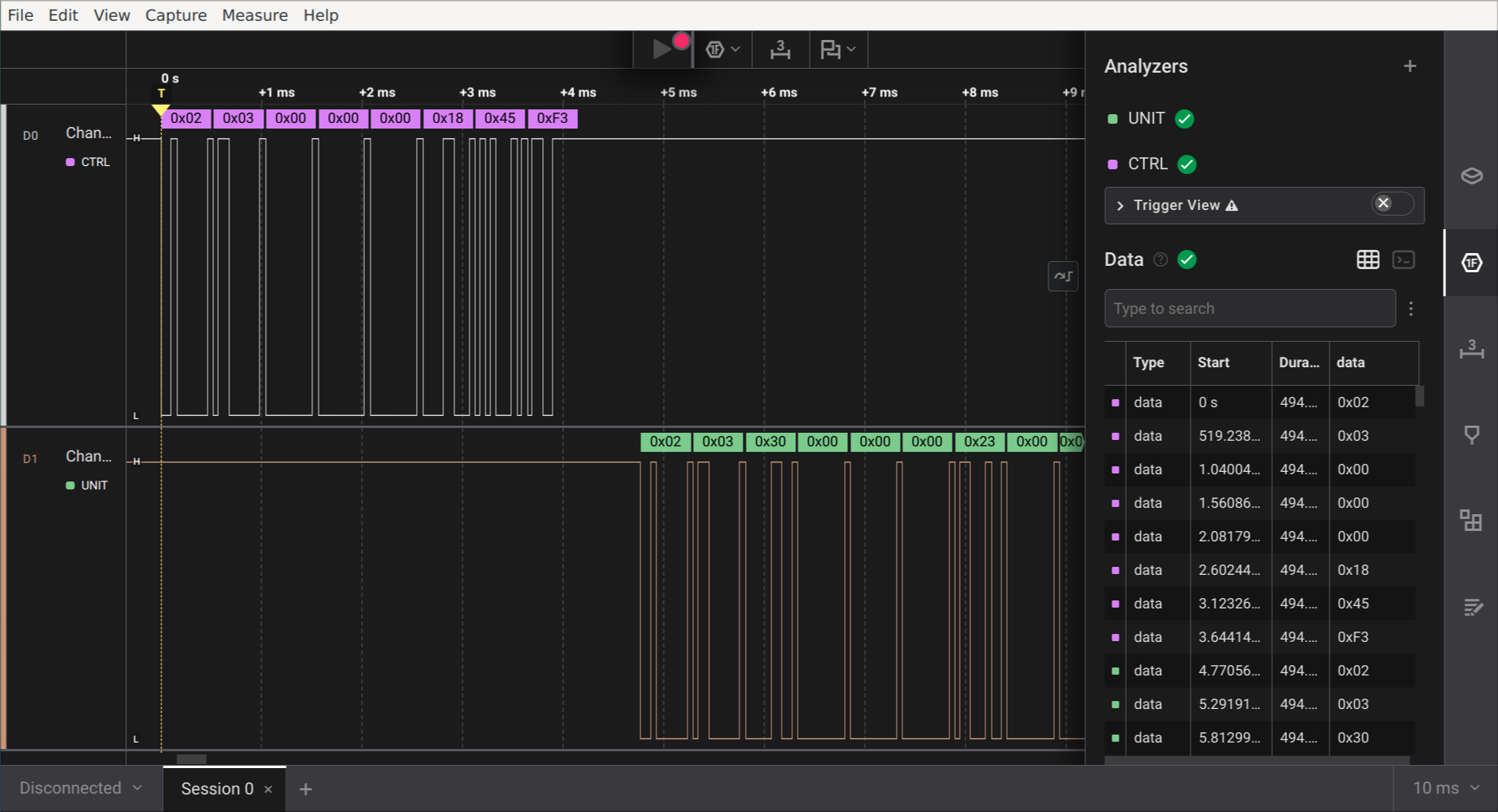

Captured traffic between the controller and

base unit in Logic 2.

Captured traffic between the controller and

base unit in Logic 2.

Making Sense of the Bytes

Now we have a long list of meaningless bytes. Let's try to find some patterns in

it. The first observation is that the controller always starts the communication

by sending a frame to the unit, and the unit responds by sending one frame

back. When idle (not touching the controller), it keeps sending the same 8-byte

ping/status request, and the unit responds with 53 bytes. Most likely this is

the controller querying the unit status, since live data such as airflow and

motor speed is shown on the controller's screen.

If we take a close look at the request bytes:

0x02 0x03 0x00 0x00 0x00 0x18 0x45 0xF3

A good guess is that the last two bytes are some kind of checksum. Usually

engineers don't want to reinvent the wheel, so it makes sense to try a CRC

before diving too deeply into this.

crccalc.com

is a great tool to quickly calculate the common CRC variants at once, and indeed

we have a match. CRC-16/MODBUS outputs 0xF345, which is encoded as

little-endian in the request.

As mentioned, you don't want to reinvent the wheel. Since the checksum uses the

MODBUS variant of CRC-16, it's a reasonable guess that the application layer

would be Modbus RTU as well.

Modbus RTU

is a simple and common industrial protocol used to let devices talk to each

other over serial links such as RS-232 or RS-485.

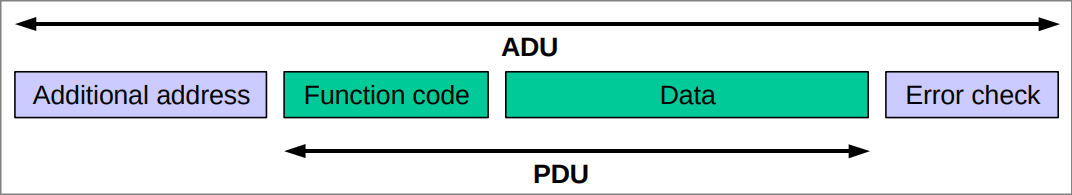

The Modbus specification defines the general frame structure as a Protocol Data

Unit (PDU), independent of the underlying transport. The PDU contains the

Function Code (what action the server should perform) and the data (parameters

for that action). The PDU is carried inside an Application Data Unit (ADU),

which adds fields such as the server address and CRC.

General

General MODBUS frame.

For RS-232/RS-485, the ADU is defined as

<Server address (1 byte)> <PDU (max 253 bytes)> <CRC (2 bytes)>

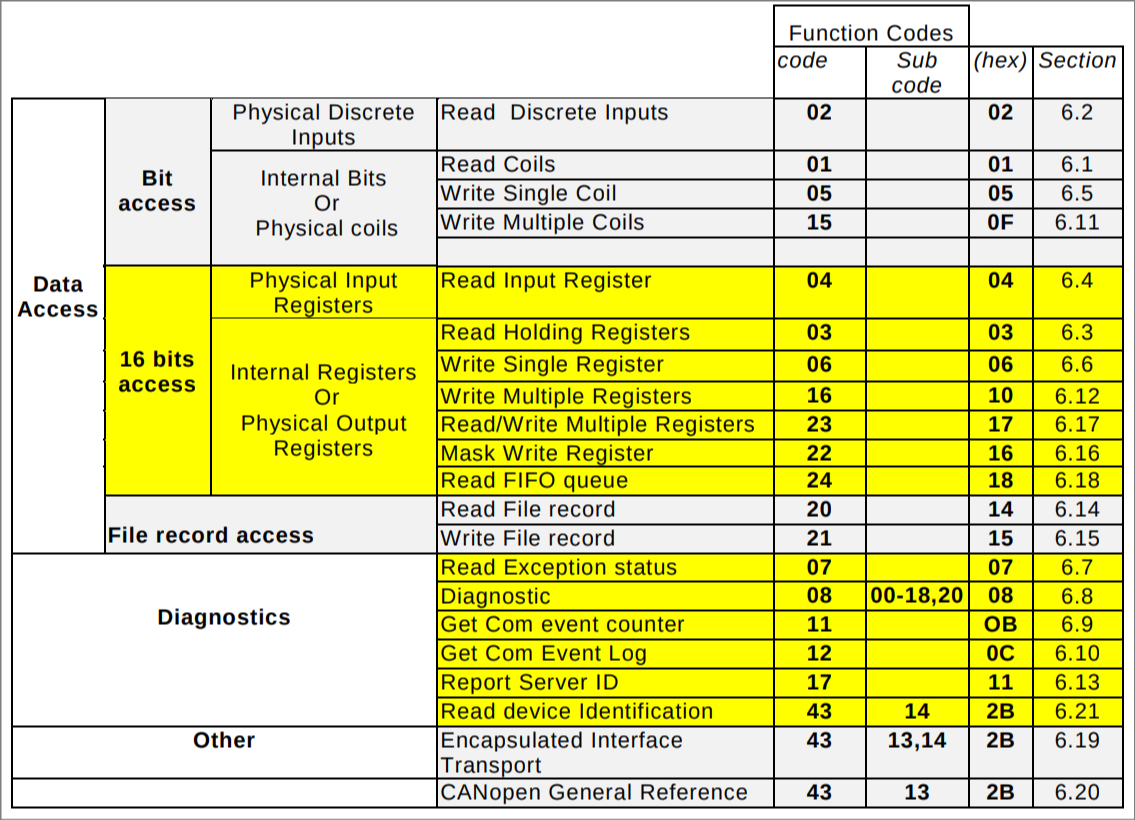

In addition, the specification describes these function codes

MODBUS Function Code

Definitions.

Our request frame matches the above definition:

0x02 0x03 0x00 0x00 0x00 0x18 0x45 0xF3

<--> <--> <-----------------> <------->

| | | |----- CRC (ADU)

| | |------------------------- Data

| |------------------------------ Function Code

|----------------------------------- Address (ADU)

The Address field in the ADU seems to always be 0x02. Based on the above

function code table, 0x03 maps to Read Holding Registers, which is used to

read the contents of multiple registers. That matches our hypothesis. The

arguments for Read Holding Registers are defined as follows:

Starting Address: 2 bytes

Quantity of Registers: 2 bytes

The register-read response frame has this structure, with each register packed

into two bytes.

Function Code: 1 byte

Data length: 1 byte

Register values: <Data length> bytes

Using those definitions, the data in the read request decodes into:

Starting Address: 0x0000

Quantity of Registers: 0x0018

and therefore the response size should be:

PDU = 1 + 1 + 2*0x18 = 50 bytes

ADU = 1 + PDU + 2 = 53 bytes

That matches as well. At this point, we can be pretty sure we're dealing with

Modbus RTU. We can treat the link as Modbus RTU and start interpreting the

register data rather than raw bytes. One parsed Read Holding Registers

response decodes into these values, which don't look random to me:

reg: 0x0000 = 0x0001 (1)

reg: 0x0001 = 0x0023 (35)

reg: 0x0002 = 0x0000 (0)

reg: 0x0003 = 0x0000 (0)

reg: 0x0004 = 0x0000 (0)

reg: 0x0005 = 0x0000 (0)

reg: 0x0006 = 0x00C8 (200)

reg: 0x0007 = 0x04B0 (1200)

reg: 0x0008 = 0x0960 (2400)

reg: 0x0009 = 0x0000 (0)

reg: 0x000A = 0x0001 (1)

reg: 0x000B = 0x0000 (0)

reg: 0x000C = 0x9600 (38400)

reg: 0x000D = 0x0000 (0)

reg: 0x000E = 0x0DFC (3580)

reg: 0x000F = 0x004B (75)

reg: 0x0010 = 0x028A (650)

reg: 0x0011 = 0x02EE (750)

reg: 0x0012 = 0x0000 (0)

reg: 0x0013 = 0x192A (6442)

reg: 0x0014 = 0x0023 (35)

reg: 0x0015 = 0x0000 (0)

reg: 0x0016 = 0x0000 (0)

reg: 0x0017 = 0x0000 (0)

Making Sense of the Registers

There is definitely less chaos now, but we're still missing the meaning of these

individual registers. Figuring them out should be straightforward: some values

already map directly to what the controller shows, such as target airflow, and

in addition, we can use the device and see which registers change (turning it

on/off, changing settings, etc.). With that approach, I came up with this

mapping. The unknown registers stayed constant across all captures and state

changes in this analysis.

| Address | Name | Units | Notes |

|---|

0x0000 | State | - | 0 = OFF, 1 = ON |

0x0001 | Target flow | m3/h | Target airflow |

0x0002 | - | - | Observed 0 |

0x0003 | - | - | Observed 0 |

0x0004 | - | - | Observed 0 |

0x0005 | - | - | Observed 0 |

0x0006 | P-Filter limit | km3 | Maximum airflow rate |

0x0007 | M-Filter limit | km3 | Maximum airflow rate |

0x0008 | C-Filter limit | km3 | Maximum airflow rate |

0x0009 | - | - | Observed 0 |

0x000A | Communication address | - | Modbus device address |

0x000B | - | - | Observed 0 |

0x000C | Baud rate | - | Communication baud rate |

0x000D | Beeper | - | Beeper state |

0x000E | Speed | rpm | Fan speed |

0x000F | Tube diameter | mm | Tube diameter |

0x0010 | - | - | Observed 650 |

0x0011 | - | - | Observed 750 |

0x0012 | - | - | Observed 0 |

0x0013 | - | - | Observed 6442 |

0x0014 | Real flow | m3/h | Measured airflow |

0x0015 | - | - | Observed 0 |

0x0016 | - | - | Observed 0 |

0x0017 | - | - | Observed 0 |

The table still has many unknown registers, most of which are zero. Three of the

zero-valued registers likely belong to the filters' airflow counters. However,

my counters still show zeros, so it's not possible to map them yet. In addition,

the user manual defines three different error states. I have no idea whether

there are individual registers for those errors, or just a single one.

Changing the State

There isn't much to setting the registers. The controller uses the Write Single

Register (0x06) function to write a 16-bit value into a specific register.

The request has these arguments:

Register Address: 2 bytes

Register Value: 2 bytes

The response is an echo of the request. For example, setting the target airflow

to 36 m3/h (0x0024) looks like.

0x02 0x06 0x00 0x01 0x00 0x24 0xD8 0x22

<--> <--> <-------> <-------> <------->

| | | | |----- CRC (ADU)

| | | |--------------- Register Value

| | |------------------------- Register Address

| |------------------------------ Function Code

|----------------------------------- Address (ADU)

Similarly, toggling the power uses register 0x0000 with 0x0001 for ON and

0x0000 for OFF.

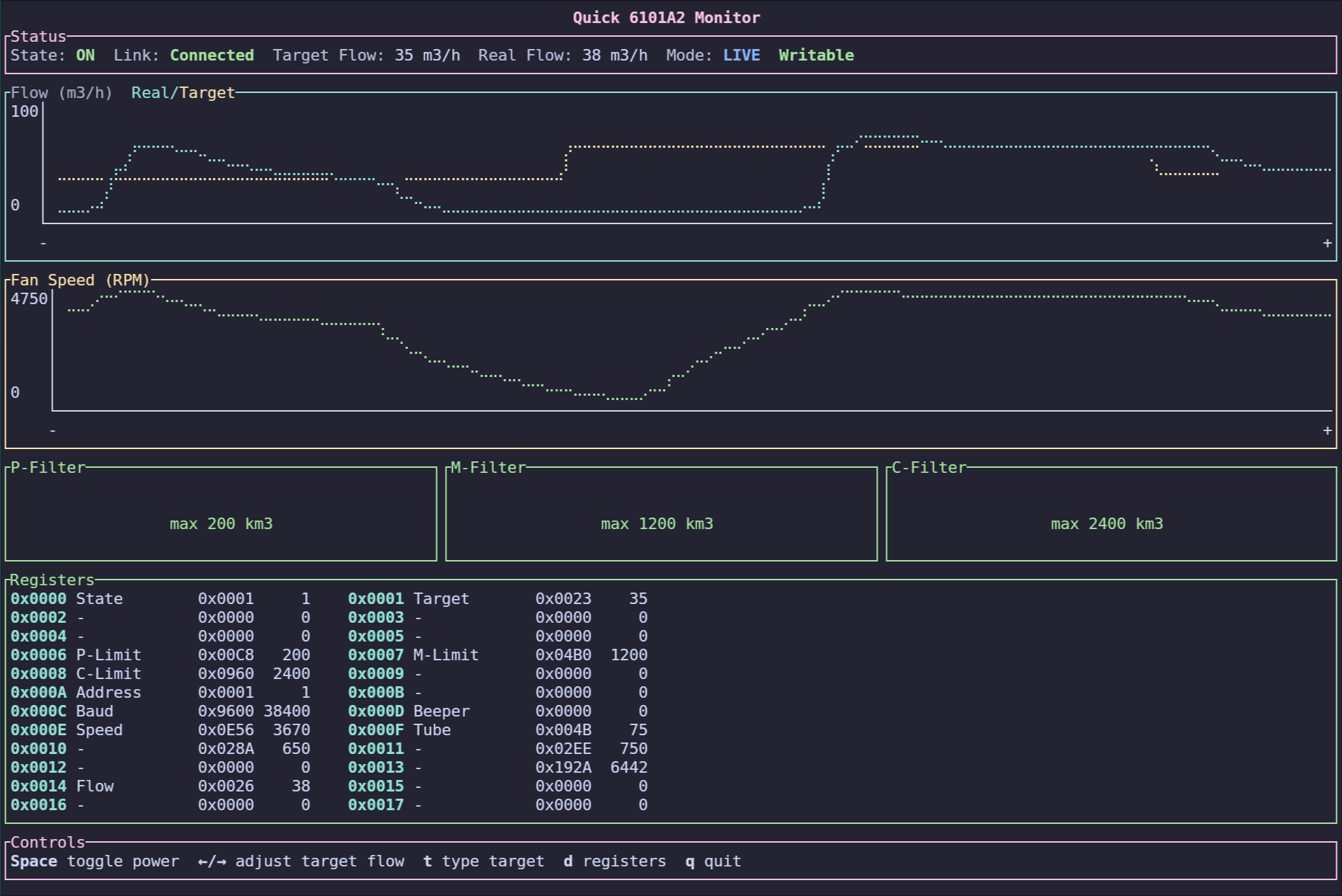

PoC || GTFO

Let's put the above pieces together and create a PoC terminal monitor to

interact with the fume extractor. The

modbus-rtu crate actually takes the

heavy lifting by implementing the Modbus RTU protocol for us. So, our job is

pretty much just to parse the correct registers and show them in the UI. The

monitor shows power state, target flow, real flow, fan speed, and register

values in real time. You can find the source on

GitHub.

Terminal Monitor for Quick 6101A2.

Terminal Monitor for Quick 6101A2.

Future Work

This is the end of part 1 of reverse engineering the Quick 6101A2. Figuring out

the controller protocol gives us a solid foothold to understand the device

internals. Next I want to take a closer look at the external tool connection and

try to dump the main unit firmware to figuring out the purpose of the unknown

registers. In addition, I also still need to build the proxy device so my

soldering and hot-air stations can turn the fume extractor on automatically.